One of my friends recently retired at age 30. I was amazed.

How did he do it?

Why did he do it?

And most importantly, what is he going to do with all his newfound time?

To be honest, his investment strategy is pretty standard. I was more interested in the psychological aspect of retiring early, so I asked him more.

And more.

And more.

And I recognized that retiring that young requires some unique life choices. Not everyone is comfortable with them, and that’s okay!

I don’t think everyone can or should copy him. I certainly didn’t. But I thought my friend’s story was so unique that it needed to be shared with the world. He agreed to write the article below anonymously.

So, here it is. The secret has been revealed: How you can retire at age 30, as written by my friend.

A 5 Point Plan to Retiring at 30

When I was a kid, I didn’t understand why people wanted jobs. I’d hear news stories about people fighting for jobs and wonder, “Don’t adults always complain about having to go to work? Why do they want to spend one third of their time doing it? Why don’t they fight for stuff instead?” Obviously, there’s more nuance to these questions than I understood back then, but there’s still insight to be gained in trying to answer them.

With time, that line of questioning grew to form a core tenant of my personality. I don’t see work as something people should have to do, in and of itself. There’s no virtue in being busy. To me, work is a means to an end. It’s a way to satisfy the improbable physical requirements of staying alive, in a universe that doesn’t care if you manage to. This isn’t to say that everyone is owed material comfort, only that we should invest in producing those comforts as efficiently as possible, with a minimum of ongoing work. That way, everyone could spend a lot more of their lives on whatever makes them happy.

As things stand, we’re a long way from that kind of world. But by the time I finished school, it seemed realistic that I myself could live by those ideals. With good luck, a minimalist outlook, and (yes) some work, it would be possible to recover a huge fraction of my life to spend however I wanted. The result, I hoped, would be to maximize my total happiness over time.

Years later, all those pieces fell into place, and I decided to retire at 30. This approach wasn’t really planned, so much as felt out along the way, and could definitely be optimized. It’s also not something I’d suggest to everyone, since it requires lifestyle choices that might not match your needs. Finally, this is a lifelong plan that’s less than halfway through, so I can’t promise you it’s going to succeed.

And now, to stop burying the lede, here’s my personal 5 point plan to retiring at 30, and hopefully maximizing my cumulative happiness:

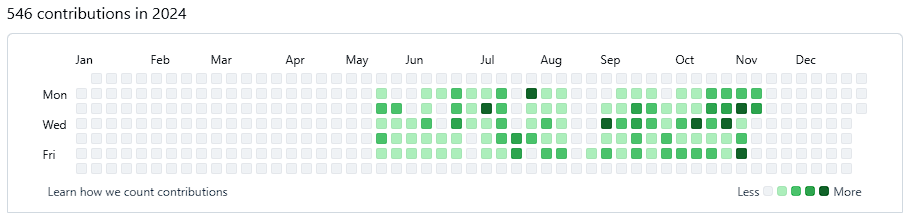

- Be a SWE in Big Tech for 8.5 years

- Be a non-US-citizen willing to return home

- Never ever have children

- Live like a person with ¼ of your pay

- Die before age ruins your quality-of-life

Be a SWE in Big Tech for 8.5 years

Retiring takes money, ideally a lot of it. The way I happened to get that money was by joining a Big Tech company straight out of school. This wasn’t a crazy startup scheme where I got a bunch of stock options for joining and then the company had a meteoric IPO. Instead, I interviewed at an established company and was hired into an entry-level software engineer position.

Some of this story is based on skill (I’m a pretty good developer!) but it would be dishonest to ignore luck. I graduated school in 2016, which was a booming time for the industry. Fortunes were being made, demand for talent was high, and everyone was learning to code. It was, in retrospect, a relatively easy time to get an offer and start saving. This was something professors definitely tried to impress on us, but not something my foolish teenage-self took to heart.

One detail in particular really convinces me that my outcome was a product of the times: how I got the interview. During our last year of university, a friend of mine and I were chatting before a lecture. This friend mentioned he’d been contacted by a recruiter and that the recruiter had asked if there were any other classmates they should reach out to. Offhandedly, I mentioned I was interested and asked my friend to pass my name along. That was, to my recollection, all the thought I gave it, until the recruiter actually did contact me to start the formal interview process.

To this day, I wonder how my life would be different if that chance conversation had gone any other way. What if my friend hadn’t mentioned the recruiter? What if I hadn’t suggested myself? What if my suggestion had been ignored or forgotten? Given the environment, things would likely have followed a similar course regardless, considering how aggressively new-grads were being pursued. Regardless, I still pause at the possibility that my whole life-trajectory hinged on this one accident, which I would never have recognized in the moment.

But to return to the larger picture, landing a Big Tech job provided a lot of money in a relatively accessible, low stakes way. Over 8.5 years, I was able to put away about 2 million USD, following a pretty unremarkable career path. I didn’t play office politics, never had to swallow (or even face) ethical dilemmas, and was promoted exactly twice.

This point of the plan obviously changes as industries rise and fall, and I understand not everyone is cut out to do programming. However, this was a key part of my plan, and tech is more than writing code. I believe a lot of people reading this could replicate the approach.

Be a non-US-citizen willing to return home

I’m Canadian and Big Tech was in Silicon Valley. The US is an expensive place to live.

Housing, healthcare, education, and daily staples all cost an inordinate amount in the United States, especially in areas with tech jobs. Canada certainly isn’t cheap either, but it has a lot of cost advantages. Most countries are less expensive in several of these categories.

For example, in London, Ontario (a.k.a. Fake London), there are multiple neighborhoods with homes under 500k USD. These range from new construction to 19th century, high-rise to detached, 1-bedroom to 4. This is a city of nearly a half million residents, with a major university, and options for arts, culture, and recreation.

At that same university, my engineering degree (admittedly a few years ago now) cost about 35k USD. This was for a competitive program, recognized anywhere in the world. It was possible because of government support for education (and my parents’ foresight).

Similar government programs make healthcare effectively free to all residents (although the Ford provincial government is trying to undermine this). Yes, the funding comes from taxes. And yes, not every procedure is covered. But in general, medical bills are not something Canadians think about.

My point here is that, by moving to another country, you can reduce your expenses without reducing quality of life. I did this by returning to Canada. Relocating is easiest if you’re already a citizen somewhere else (as in my case), but US-citizens can pursue emigration.

Never ever have children

This one is exactly what is says on the tin. Having kids makes retirement much harder.

For starters, kids are expensive. I estimate (unverified!) each one adds 20-30% to your cost of living. Housing, food, transportation, entertainment. They’re a whole tiny human that needs most of the same stuff as you, plus a bunch of extras specifically because they’re still developing.

Children also create second-order costs. For most couples, there’s a decision between daycare vs homemaking, which pauses someone’s career and income (although if you’re following this plan, point #1 makes the choice easy). Thinking more broadly, grocery runs suddenly “need a minivan”, some neighborhoods become “too colourful”, and international moves get postponed until “next school year”. All of these are fair compromises, but they unquestionably create retirement hurdles.

For me specifically, having kids is a non-issue. I don’t have any desire to be a parent, so their absence isn’t a sacrifice. I’m also gay, so there’s no way I’m getting a kid accidentally. And as a bonus, nobody expects children or grandchildren from me; I’m already way off script.

Lots of people get incomparable joy from raising kids. My goal here isn’t to deprive anyone who wants that experience. Simply, for my plan, and anyone else following along, you’ll get a lot further without a stroller.

Live like a person with ¼ of your pay

Once you get some money, the next critical step is keeping it. It’s alarmingly easy to increase spending in proportion with income (a.k.a. lifestyle inflation). If you’re incautious, you can find yourself treading financial water, never getting closer to your retirement goal.

Fortunately, the solution is simple, at least in theory. Remember that most people never have a Big Tech income, but they’re not living in the gutter. They have healthy food, warm homes, fulfilling relationships, and the occasional luxury. Copy them! With a much higher income, you can afford all of that, and also save a huge amount for the future.

Looking at expenses over my working life, I seem to have spent about ¼ of my post-tax earnings each year. For context, this roughly matches the take home pay of a dental hygienist. Because the US income tax brackets are progressive, we can approximate the additional tax I was paying as covering a hygienist’s 401(k) contributions, which would finance a standard retirement. This is the rough calculation that provides the phrasing for point #4.

Budgeting this way was sort of like getting 4 years of living for every 1 year of work. Working at Big Tech for 8.5 years mirrors a respectable 34 year career cleaning teeth.

The approach I’m outlining here also depends on an idea I’ll call “the cost-quality curve”. Basically, it’s the observation that luxurious things are much more expensive than nice-enough things. This relationship seems to be exponential, such that a one step increase in quality entails a multiplication in price. Think of when you’ve experienced this with plane tickets, fancy restaurants, or designer clothes. The trick is to live at the “sweet spot” along the cost-quality curve, where quality is reasonable but price hasn’t exploded.

To be clear, I’m not advocating that everyone can or should save 75% of their income, or that dental hygienists are the Platonic ideal of cash flow. These are numbers and comparisons that worked for me; your standards, or timeline could be different. However, if you are able to adhere the other steps, this one makes them significantly more powerful. Remember, most people are mostly happy!

Die before age ruins your quality-of-life

This is definitely the most contentious point of the plan. Whenever I talk about it, I have to agonize over the phrasing, to prevent people from assuming I’m crazy or becoming adversarial. I think it’s because it strikes at their mortal terror: the cognitive dissonance of knowing everyone dies but not believing it will happen to you.

To be brief, I plan to die much younger than most people would expect to. This isn’t an abstract hope, but a premeditation. The particular age I have in mind isn’t important (and I think it distracts from the overall presentation), but it’s certainly less than my maximum possible age.

The idea described here is very similar to the concept of “memento mori”, a Latin phrase that translates to something like “remember you will die”. I choose to interpret this as an invitation to “eat, drink, and be merry”, rather than a reminder to “atone for your outstanding sins”. I also think it would make a great tattoo, if I actually spoke Latin.

Here are my reasons for planning my own death, sorted by significance, and which I hope you’ll give a fair hearing.

- Being old seems awful. Your body fails. Your mind fails. There’s a litany of pills and tests, aches and pains. Quality-of-life goes downhill fast. I don’t especially want to live through that, and I certainly don’t want to mortgage my youth to get old-age as the reward.

- Becoming elderly isn’t guaranteed. Many people die young, at least younger than they expected. Anyone can be hit by a truck. Anyone can get cancer. I would prefer to plan my death, and race that deadline to accomplish my dreams, rather than be blindsided while daydreaming.

- When you plan your death, you control your maximum possible age. It becomes easier to predict how much money you’ll need, and the amount becomes adjustable. It’s morbid, but it’s something every financial planner asks about.

- Old-age is often expensive. As your body fails, medical costs can skyrocket (especially if you don’t follow point #2). Planning to die before a serious illness, rather than because of it, means you can ignore it in your budget.

- What will the world be like when you’re finally old? Will it be a world you want to live in? As a global civilization, we face a lot of environmental challenges, which we can’t make good predictions about. Simultaneously, we face a lot of political challenges, which based on historical evidence, won’t be resolved comfortably. I’m hesitant to stake too much on any plan that pays off decades from now.

There are some other minor considerations, like getting a living funeral, but the main ones are presented above. If you take nothing else from reading this plan, I really hope you can engage with this particular point, and think through what a “good” death means to you.

I’m not saying everyone should use euthanasia, and I’m not saying that there’s a single “correct” age for everyone to die. What I’m saying is that these things are right for me, and other people could benefit from them too. Planning how I’ll die helped me plan how to live.

Conclusion

That’s it. That’s the entire plan. If you stick to these 5 simple steps, you too can retire at 30!

With my abundant spare time, I’m not entirely sure how to spend it, but so far it’s been a lovely vacation. I’ve taken up baking, running, reading, and overall spent many evenings with old friends. If this were the rest of my days, I’m not sure I could complain.

Of course, I was told many times “you retire to something, not from something”, so I have ideas for longer term plans. In particular, I’m considering grad school and politics. My doctoral friends all say the worst thing about getting a PhD is being broke, which appears to be a non-issue. Alternatively, I feel like I could make a real difference as mayor of Fake London. Who knows!

If you’re looking for steps on what to do with your free time, I’m afraid you’re reading the wrong instructions. From here on out, this is my life, nobody else’s!

That was wonderful to hear. I wish my friend the best in the next stage of his life.

And I hope you, dear reader, take some time to contemplate your own life and career. Whether your path is conventional or not, I hope it brings you everything you wished for.

Opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Sheldon “Don” Sandbekkhaug.

You must be logged in to post a comment.